Morocco’s imperial cities are four historic capitals that, in different eras, held the country’s political and symbolic center of gravity: Fez, Marrakech, Meknes, and Rabat. Each one is a capital in its way, with its own dynasty, urban personality, and signature monuments. With Maratrek, they tell the story of Morocco as a meeting point of Berber, Arab, Andalusi, Saharan, African, and Mediterranean influences, shaped over centuries by trade, scholarship, empire-building, and the everyday creativity of city life.

Imperial Cities

To travel through the imperial cities is to move through layers of time, from medieval labyrinths of stone and cedar to grand ceremonial gates, tiled courtyards as well as fountains to wide boulevards and modern ministries, from bustling markets to quiet gardens where the call to prayer seems to hang in the air a second longer. Fez is often described as Morocco’s spiritual and intellectual heart, and it earns that reputation the moment you step into the old city, Fez el-Bali.

Founded in the late eighth and early ninth centuries, this one among imperial cities grew into one of the great urban centers of the Islamic West, linked to learning, craft, and commerce. The medina is famously dense and intricate, a place where streets narrow into passageways, then open unexpectedly into small squares, mosques, and workshops. Fez is also associated with scholarship and religious life, including madrasas with carved stucco and zellij tilework, libraries, and old institutions of learning that helped anchor Morocco’s identity as a center of jurisprudence and theology.

Yet Fez is not only solemn within imperial cities, but intensely alive. Copper is hammered into trays, leather is dyed and stitched, wood is inlaid, and spices pile into fragrant pyramids. What makes the city distinctive is how its medina still functions as a living organism rather than a museum. It can feel like a masterclass in urban continuity, where medieval architecture and modern routines interlock, and the crafts are not decorative add-ons but an economic and cultural bloodstream. When people speak about authentic Morocco, they often mean the immersive, intricate, workaday grandeur of Fez.

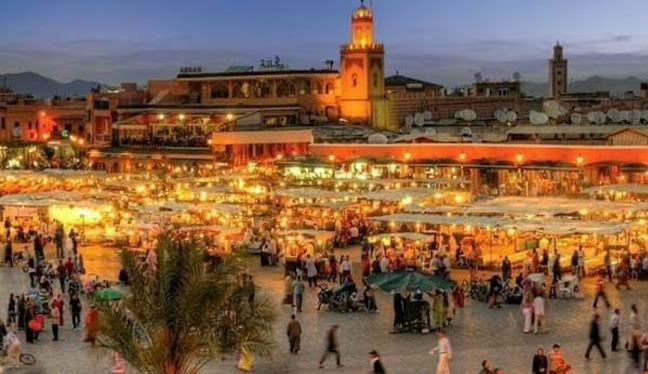

Also among imperial cities is Marrakech, which, by contrast, projects a sun-warmed charisma that feels theatrical, sensual, and open to the desert. Founded in the eleventh century and shaped profoundly by the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, Marrakech became a major imperial capital and a gateway between Atlas Mountains, Sahara, and the broader Mediterranean world. Its visual signature is the warm red-pink hue of its walls and buildings, which glow at different times of day like a living palette.

Marrakech is also a city of spaces, with wide courtyards, monumental minarets, gardens, and large public squares. The famous central square is less a single place than a daily performance where storytellers, musicians, food vendors, and passersby create a constantly shifting scene. Among imperial cities, Marrakech has a quieter elegance that reveals itself in riads and palaces, where plain exterior walls hide interior worlds of tiled fountains, orange trees, and patterned light.

The city’s relationship with gardens is especially telling. In a climate that makes shade and water precious, gardens are both luxury and philosophy. They are controlled nature, a statement of order, and a refuge from heat and noise. Marrakech has the feeling of imperial cities in its confidence, a city that wears its history with flair, inviting you to watch, listen, taste, and wander. Meknes is often the most underrated of the four, but it holds one of the clearest expressions of imperial ambition.

It rose among imperial cities under Sultan Moulay Ismail in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, when the city was transformed into a grand capital meant to rival the great courts of the era. It has an architectural temperament that differs from Fez’s intricate density and Marrakech’s theatrical openness. Meknes feels more measured, spacious, obviously planned in its monumental elements. The city is known for its impressive gates, walls, and large-scale construction that speak to the sultan’s desire to project authority and permanence.

Holding the project of imperial cities, Meknes also had a practical side. Fortifications, granaries, stables, and administrative complexes were built to support a centralized state. In there, you can sense how power wanted to be seen, how order was expressed in stone and scale. At the same time, Meknes retains a human pace. It is a city where you can experience the imperial layer without being swept away by crowds, where the medina feels navigable, and where the surrounding region adds depth, with fertile plains, vineyards, orchards, and nearby archaeological remnants that broaden the historical horizon.

Meknes is a reminder that Morocco’s imperial cities are not only about beauty, but also governance, security, and the material infrastructure of rule. Rabat, the current capital, completes the quartet with a different kind of imperial identity. One rooted in statecraft, diplomacy, and the modern nation, yet still anchored in deep history. Rabat’s role as an imperial city is tied to earlier dynasties and strategic coastal importance, but its present-day character comes from the way it blends administrative modernity with historic neighborhoods.

The city feels calmer and more expansive than the older imperial cities, with wide avenues, official buildings, and a rhythm shaped by government and institutions. Still, Rabat is not merely bureaucratic. Its historic areas, including the old medina and coastal fortifications, preserve the sense of a city that has long faced outward toward the Atlantic world. Rabat’s appeal lies in its balance. It is a place where contemporary Morocco is on display in a straightforward way, yet the past remains visible in walls, gates, and waterfront viewpoints.

The coastal light, breeze, and sense of space give Rabat a distinct atmosphere among the imperial cities, suggesting a Morocco that is both rooted and forward-looking. What unites the four ones is not a single architectural style or a uniform historical narrative, but the idea of a Moroccan state as a continuity that shifts centers without losing itself. Dynasties rose and fell, trade routes expanded as well as contracted, and foreign pressures arrived from multiple directions, yet the imperial city remained a stage where legitimacy was performed through mosques, palaces, walls, public works, and patronage of learning and craft.

These imperial cities also show how Moroccan identity was never purely one thing. In Fez you feel the pulse of scholarship and artisanal mastery. In Marrakech, the crossroads energy of mountains and desert. In Meknes, the deliberate assertion of centralized power. In Rabat, the administrative present that carries historical echoes. To speak about them is to testify Morocco’s talent for synthesis, taking diverse influences and making them coherent without flattening them.

For visitors, the imperial cities offer different ways to understand Morocco. Fez rewards patience and attention to detail. Marrakech is about curiosity and appetite. Meknes is for those who want the imperial story without the rush. Rabat rewards those who want to see how history sits inside a modern capital. For Moroccans, these cities are not only tourist icons but living references, places that anchor memory, pride, and deep regional character.

The imperial cities are, in the end, less about the past as a finished chapter and more as a daily companion, visible in stonework and street plans, heard in the cadence of marketplaces and prayer, as well as felt in the enduring magnetism of places that once held a kingdom together and still help define what Morocco is.